It was my first trip to Asia and my first day in Kathmandu, Nepal’s capital. After hotel check-in, I made a beeline to the traditional market area. I walked among temples, big sculptures, numerous ceremonial sites — and an awfully lot of people. The crowds kept growing with folks gathering on the steps of the public structures as if at a stadium.

I had arrived on the fifth day of the eight-day Festival of Indra Jatra, the rain god. A central part of the celebration is a procession of three golden “chariots,” one carrying the “living goddess,” who is, in reality, a young and mortal girl.

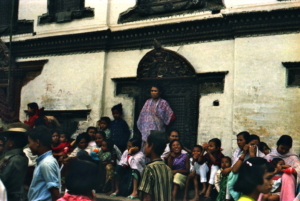

Locals gather to watch the Festival of Indra Jatra, the rain god, in Kathmandu, 1970.

Above, Temple of the Living Goddess, seen in 1978 when it was easier to get photos. Skies were also bluer on that visit. Below, a Kathmandu city center scene.

But before I saw any of the main procession, I spotted a torchbearer leading a small contingent, which included at its head three masked dancers and a drummer. As the dance group broke up, onlookers reached out to touch the performers.

Walking further, I found a man spraying water at the crowd. Then a papier mache elephant led by a man with torch charged into and out of the crowd. I took a slight hit from that.

I next found the largest of the golden “chariots,” which looked to me more like a floating pagoda than a chariot. A number of men, pulling two ropes, moved the thing onto a sort of temple platform. A man appeared to be handing something down to people in the crowd (maybe coins?), seemingly from the “goddess” seated well above the rest of us. This generated some fun and a great squabble.

The event was exotic, fascinating and, by my standards, also chaotic.

Monkey Temple, Kathmandu, which has no connection to this blog other than I like it.

I had expected none of this activity in Kathmandu. Furthermore, my trip, taken in 1970, coincided with other bigger events that had little effect on my journey. On Sept. 6 and 9 of that year, a number of Palestinians collected hostages by hijacking four airplanes, three meant to go to New York.

Pan Am’s 747 was forcibly landed at Cairo on Sept. 6 and destroyed the same day. The other three were still parked at an obscure landing site in Jordan when I flew through the neighborhood on Sept. 11; they were destroyed on Sept. 12.

The trip home was atypical, too. Egypt’s president Gamal Nasser had died. His funeral, on Oct. 1, drew massive numbers of mourners to Cairo and produced real chaos, with at least 46 killed in the crush. My flight home took me through Cairo on Oct. 2. Passengers were not allowed off our plane during the layover, but some government delegations to the funeral boarded and left Cairo with us. I can only imagine that the airport was chaotic that day, too.

Over the years since, my itineraries have dropped me into other unexpected situations. Diaries and photos helped with recollections of Nepal’s festival, above, and of other surprises, as follows.

1972: Independence Day, Indonesia. I flew into Medan on the island of Sumatra on Aug. 17 having no idea this was Indonesia’s Independence Day. That meant there were virtually no services at the airport, but I somehow managed to arrange to be picked up and driven to the office of Seiba Tours, which fortuitously was open.

My diary says I was “brought to the city in a mess of people and vehicles.” In another stroke of good luck, the tour company’s office was right on the route for the day’s celebratory parade.

So, I spent an hour or two literally leaning on the doorjamb as I watched and photographed the passing marchers. This show included lots of military and school groups, but of most interest to me, there were numerous groups in traditional costumes from various regions or Indonesian islands.

Marchers in Indonesia’s Independence Day parade wearing traditional garb of the Karo people, who hail from the province of North Sumatra in Indonesia.

Men of Nias Island at Indonesia’s Independence Day parade, in Medan, capital of the North Sumatra province on Sumatra. Some carry spears; Nias men are known for their war dances.

1983: Coptic Orthodox Easter. I had already been booked to Egypt and North Yemen when I learned I would arrive in Cairo on the Saturday of Orthodox Easter weekend.

With that bit of warning, I arranged to be picked up on arrival day, almost immediately after hotel check-in, and transported to the city’s humongous St. Mark’s Coptic Orthodox Cathedral.

Coptic Easter ceremonies were to begin two or three hours before midnight on the Saturday night, with the mass itself lasting another two and a half hours or more, beginning at midnight. I attended the part that occurred before 12.

Men sat on one side and women on the other. A woman behind me periodically gave instructions, very cordially, advising when to stand and also advising me not to cross my legs during a church service because that was considered improper.

Chanting priests walked the length of the church and circled the altar a number of times, with at least one swinging a censer and leaving a trail of incense. The chants were not music as Westerners describe it, but the Copts characterize the chanted liturgy as a symphony.

The pageantry also included a procession down the center aisle led by a bishop and priests in gold and white vestments, followed by a score of young white-robed seminarians and other worshippers, some bearing tall staffs topped with heavy Coptic crosses.

Bishop and priests who led services that preceded Easter mass in Cairo’s St. Mark’s Coptic Orthodox Cathedral.

The bishop’s distinctive golden vestments are seen most vividly here.

Procession participants assembled near the altar in Cairo’s St. Mark’s Coptic Orthodox Cathedral toward the end of services that preceded Easter mass.

As I left around midnight, it was a madhouse outside the church door with children and adults in Easter finery running around and making lots of noise.

The drive out of the cathedral compound was equally mad, with way too little room for the traffic. I was certain my driver would hit someone. But he didn’t. Then, I spent the ride to my hotel hoping my tailgating driver would not have an accident! He didn’t.

2000: War in Ethiopia. I attended a travel industry conference in Addis Abba, Ethiopia’s capital, and had plans for additional touring. Over four days, I was to have flown to historical sites to the north, then return to Addis for my flight home.

However, a simmering war between the central government and then-secessionist Eritrea heated up; the government canceled all flights to the north and, thus, drastically changed the nature of my travels.

The place I most wanted to see was Lalibela, a former capital at about 8,630 feet above sea level and site of fabled medieval Ethiopian Orthodox churches, 13 of them, carved from rock and situated below ground.

Above, view of the cross-shaped top of the rock-hewn St. Giorgis (St. George) Church in Lalibela, Ethiopia. Below, a fuller view of St. Giorgis, which is nearly 40 feet tall.

Getting there by car would require 16 hours each way including meals and photo stops, leaving me a total of five hours for Lalibela sightseeing. I paid my tour provider a surcharge for this truncated version of my itinerary, but with a car and driver. Accommodations found to and from Lalibela were rock-bottom spartan.

Priest at the small Beta Meskal (House of the Cross) rock-hewn church in Lalibela, Ethiopia.

Traditional two-story round house in Lalibela, Ethiopia

At the time, I wrote a newspaper column reporting the following:

* We were stopped at a police security point at Kombolcha and asked to show my permit to travel north of Addis. I had none. Nearly two hours later, when the police chief gave permission to proceed, I was standing in a tiny room at a tiny police station, jammed full of people. I counted 14 men besides my driver, at least 12 of them onlookers. One rested on a cot, his head on his monster gun. It turned out only journalists needed the travel permit, but no one asked my profession.

* We stopped for many photos, especially of women because they wore traditional dress and often elaborately braided hairdos. Once, 10 young Oromo women posed in a line until the clicking stopped. All sported the intricate cornrows.

Above and below, young women who agreed to be photographed at one of several impromptu roadside stops during a drive across Ethiopia. As I took photos, the group got larger.

* On the last day, we stopped at a market. I photographed women, some with tattoos on their faces, and my driver bought a lamb for $5, $2 off Addis prices. The lamb rode the last five hours to the Addis airport inside our Land Cruiser — because I refused to let the driver tie him to the roof.

Two young women seen in the market town visited en route back to Addis Ababa.

Others: This is getting too long. A separate posting will deal with surprise events in Europe.

See more about Egypt and Indonesia at BestTripChoices.com:

https://besttripchoices.com/egypt/

https://besttripchoices.com/indonesia/

This blog and its photos are by Nadine Godwin, BestTripChoices.com editorial director and contributor to the trade newspaper, Travel Weekly. She also is the author of “Travia: The Ultimate Book of Travel Trivia.”